“Dr. Chaffin, I started working at a new blood bank recently, and I think they are breaking the rules! A patient came into the emergency room after an auto accident, and the FFP given to him was blood group A! Isn’t AB the ‘universal plasma,’ not A? The patient happened to be group O, so type A FFP turned out to be just fine, but I am worried! Are we doing the wrong thing?”

This exchange illustrates one of the things I love most about blood bankers: They pay attention, and are always on the lookout for unsafe practices. In this case, though, the use of group A plasma transfusions in emergency transfusions is absolutely okay. Despite how wrong it might feel, use of group A FFP in emergency settings is a growing trend – and a good one, for several reasons.

Standard Blood Bank practices

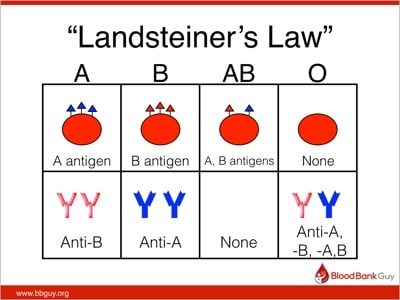

Ever since Dr. Karl Landsteiner described the ABO blood group system in 1901, we have used his findings to define “safe transfusions.” In the ABO blood group system, a person carries either an A or B antigen, both, or neither on his red blood cells, and the opposite antibodies in plasma (this is “Landsteiner’s Law”).

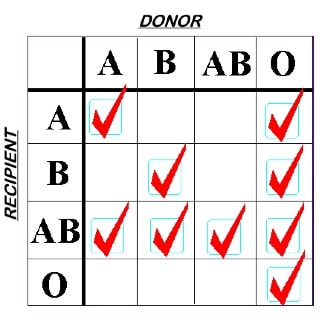

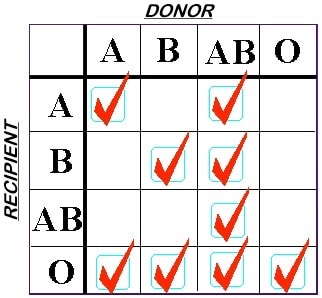

When transfusing red blood cells (RBCs), blood bank standard practices are designed with the aim of protecting the integrity of the transfused red blood cells. As a result, RBCs should not be transfused to patients carrying incompatible ABO antibodies (e.g., don’t give group A RBCs to a group O recipient, since the recipient’s strong anti-A will destroy the transfused RBCs). A significant proportion of the fatalities reported to the FDA from incompatible transfusions are a result of someone accidentally exposing transfused RBCs to incompatible recipient ABO antibodies. On the other hand, we don’t worry about the small amount (typically less than 50 mL) of potentially incompatible plasma that might be infused along with the RBCs (for example, when a group O RBC is given to a group A recipient); that amount is typically not enough to cause much trouble. The very familiar rules look like this:

ABO Rules for RBC Compatibility

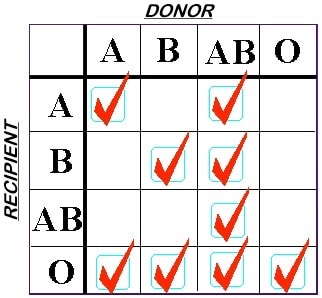

The rules are switched when we choose plasma components for transfusion. We select Fresh Frozen Plasma (FFP) or Plasma Frozen within 24 hours of collection (PF24) units with the intention of protecting the recipient’s RBCs. This is because we are infusing anywhere between 250 and 400 mL of plasma, which contains ABO antibodies, making this scenario significantly more scary than transfusion of smaller amounts of plasma in an RBC transfusion! Note especially that group A donor plasma is only compatible with group A or O recipients, by these rules.

ABO Rules for FFP Compatibility

Platelet transfusions cross ABO boundaries

A blood bank would never routinely choose to issue a unit of group A plasma for a group B recipient because of Landsteiner’s Law. However, we have essentially done exactly this with platelet transfusions, safely, for YEARS! Let me explain.

Unfortunately, blood banks often don’t have enough platelets to go around, let alone adequate supplies to provide ABO-identical platelets for each patient! As a result, most transfusion services accept a somewhat higher degree of risk for out-of-group platelet transfusions than they ever would for plasma-only products. It’s like acquiescing and accepting the risk of allowing your child to walk to school because the risk of harm from having them drive with their eager, teenaged, just-licensed older sibling is greater.

Imagine this situation: The blood bank only has 1 unit of apheresis-derived platelets in inventory, and it is group A. An order for platelets comes in from the operating room, where a testy cardiac surgeon is trying to finish a bypass procedure and wants to help his patient stop bleeding. The patient, however, is group B! Depending on hospital policy, the blood bank technologist might call the blood supplier to see if a group B platelet is available, but in most cases, the blood banker will issue that group A platelet product without hesitation (NOTE: Many hospitals screen platelet units for high-titer ABO antibodies and would not issue one with strong antibodies to an out-of-group patient. This is especially true in the Eastern part of the U.S., but the strategy is not universal). Normal-sized adult patients in this setting do just fine, with no evidence of significant hemolysis of the recipient’s RBCs (though there are some studies suggesting this practice might not be a good idea for other reasons).

Emergency plasma transfusions

In recent years, we have seen a large increase in the proportion of plasma used in emergency situations as compared to RBCs. Trauma surgeons in particular are now accustomed to transfusing their patients with plasma in a ratio of close to 1:1 with RBCs. Since group AB plasma has no ABO antibodies, it has historically been the standard choice when a recipient’s blood type is not known (pretty much the definition of an emergency transfusion). This has resulted in HUGE demands on blood suppliers to provide AB plasma in greater quantities (16.5% more in 2013 than in 2011, per the 2013 “AABB Blood Survey Report,” pg 17). There’s one massive problem, though: AB people make up only 4% of the population! When hospital blood banks try to keep 10-20% AB plasma in their freezers, blood centers really struggle to keep up (we can’t change the dynamics of population genetics, no matter how hard we try!).

So, what to do?

As a result of the increasing AB plasma demand, several academic hospitals decided to try something different. They said (I’m paraphrasing here): “Since 85% of people in the population are either group O or A, group A plasma would work for at least eight of every ten emergency transfusions! What if we provide group A plasma instead of group AB when we don’t know the patient’s type, and play the odds a little bit?” Of course, the remaining 15% or so of the population (the B and AB people) would get INCOMPATIBLE plasma as a result of this strategy. You can read the articles for details (referenced below), but that’s exactly what happened. However, none of the B or AB patients suffered clinically significant hemolysis, and there was no evidence of diminished outcomes in patients receiving incompatible group A plasma. The studies are all a little light on the number of patients enrolled (in particular, the ones getting out-of-group plasma), but the data appears to support the choice of group A FFP for emergency transfusions.

UPDATE: So, you say you want more data? Well, my friend, I’ve got just that for you. Please see Episode 036 of the Blood Bank Guy Essentials Podcast, in which I discuss this very issue with the lead authors of two papers giving LOTS more cumulative data on group B or AB patients receiving group A plasma. I’ll save you a little time: They saw no evidence of hemolysis or bad outcomes!

“But Joe,” you say, “wait a minute! Why the heck aren’t these group B or AB patients harmed by group A plasma?!” There are a few reasons, actually.

- The Male Donor Imbalance: As a result of efforts to decrease Transfusion-related Acute Lung Injury (TRALI), almost all group A plasma in the U.S. comes from male donors. In men, the titer of anti-B in group A plasma is generally low (due to the lack of stimulation by incompatible fetal RBCs during pregnancy), making it less likely the antibody will harm the RBCs of group B or group AB recipients . Some facilities using the group A strategy will run an anti-B titer on the plasma product and not use those with strong antibodies, but others have not found titers to be beneficial. (NOTE: This situation is very different, by the way, from group O donor plasma, where the anti-B is often much stronger. Also, a few group A male donors who have taken probiotics have been shown to have very high anti-B titers).

- The Dilution Factor: Transfused anti-B is diluted into the patient’s much-larger total blood volume, and as a result, it comprises only a small quantity of the total circulating ABO antibodies.

- Look At The Context: Remember that these situations are emergencies! As a result, the patient will likely be receiving lots of group O RBCs. This means there will be fewer “target” B or AB RBCs for the anti-B to attack.

- Secretors Rule: Most B or AB patients (80%, to be specific) are “secretors,” meaning they have soluble (free-floating) group B antigen in their plasma. ABO antibodies in general LOVE binding to soluble antigens (it’s a lot easier than trying to get close to a comparatively massive RBC), so many of the anti-B antibodies in non-type specific plasma will be “neutralized” by binding to the soluble B antigen rather than the recipient’s membrane-bound antigen.

So, we shouldn’t really be surprised that group A plasma works just fine as an alternative to AB. It is perfectly reasonable to consider the use of group A plasma in emergency situations where the blood type is unknown.

In The Real World

The use of group A as an automatic choice in emergency settings is growing rapidly, and I am seeing it more and more in hospitals with whom I work. I always caution anyone considering this strategy, though, that I personally believe it is essential to draw a blood sample from the patient as quickly as possible so the transfusion service can switch to ABO-specific products expediently. In the interim, group A FFP, while not truly “universal,” can be used in place of AB FFP without significant risk.

I must remind you, however, that the above does not mean that group A plasma is the right choice for all routine plasma transfusions! I have seen transfusion services try to apply this to non-emergency situations, and that is not a wise strategy! This is a practice shown safe in a specific, emergency situation. Routine plasma transfusions should still follow the ABO compatibility rules (repeated here for emphasis!):

ABO Rules for FFP

I’d love to hear your thoughts on the issue in the comments below, especially if your facility has implemented the group A plasma strategy.

Read more:

- Chhibber V et al. Is group A plasma suitable as the first option for emergency release transfusion? Transfusion 2014;54:1751-5.

- Cooling L. Going from A to B: The safety of incompatible group A plasma for emergency release in trauma and massive transfusion patients. Transfusion 2014;54:1695-1697.

- Isaak EJ, et al. Challenging dogma-Group A donors as universal plasma in massive transfusion protocols. Immunohematology 2011;27:61-65 (NOTE: Free pdf download of full issue).

- Mehr CR, Gupta R, von Recklinghausen FM, et al. Balancing risk and benefit: maintenance of a thawed group A plasma inventory for trauma patients requiring massive transfusion. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013;74:1425-31.

- Zielinski MD et al. Emergency use of prethawed group A plasma in trauma patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013;74:69-75.

We started using A for emergency plasma in sept 2015.

We’ve had a number of B and AB patient’s receive A plasma – but not yet seen any who have had any noticeable haemolysis.

As a trauma centre – being able to use our thawed A in the lab for those massive haemorrhage calls has made a difference in the speed of availablity of plasma (got to be a good thing) It was previously 17 mins from the alert of the trauma coming in now it goes out in the first MHP pack with the red cells.

We are also using less AB plasma – as most of previously for patients of unknown groups – so I’m sure the Blood service like it too!

Thanks for the perspective, Julie! Your experience sounds consistent with what has been reported elsewhere.

To BBGuy from OGuy (old guy): Great discussion, as usual. Sorry you are not sitting in the office next to me. Those were some good days. R!

Ricardo, you are the man! Thanks for writing, my friend!

We have implemented the use of A plasma in emergent cases where the blood type was unknown last year. The first two patients were in fact group B. No adverse events were reported.

Thanks for the input, Susan!

I have always read (per AABB Technical Manual, 16th edition) that Rh type matching is not required for FFP. Thank you Dr. Chaffin for that fabulous confirmation!! I am curious as what mechanisms are engaged in the Group A male donors having larger titers of Anti-B from probiotics. You don’t say!!

Lynnsey, we always think about ABO antibodies as “naturally occurring,” meaning that they do not have to be stimulated by transfusion, pregnancy, or transplantation in order to be present. However, the immune system doesn’t really work that way! In fact, group A or B antigens are present all around us, in nature and in things like bacterial cell walls. We see them as children, and develop the antibodies we are so familiar with as a result. Well, we also know that if there is actual further or more intense stimulation by those antigens, people can develop stronger ABO antibodies. This is seen often in group O mothers delivering non-group O babies; the immune stimulation of actual RBC ABO antigens can lead to stronger ABO antibodies in that mom. The same idea, apparently, applies to group A donors who take probiotics (loaded with bacteria that would contain ABO antigens as a part of their cell walls). The induction of stronger anti-B in these donors has been reported, and the direct stimulation is probably why.

I work in transfusion services at a level 1 trauma center, and we have adopted a more conservative version of this plan. we only give group A FFP to patients of unknown blood type during massive transfusion bucket (10 PRBCs, 4 FFP, 1 platelet), and only on the second bucket. this typically ensures that the patient has received at least 10 units of group O packed cells (in most cases) before we switch to giving them A FFP. we have been using this plan a few years now, and have given A FFP to several B and AB patients (we have a higher population of Bs and ABs in our area than most), and as far as I know we’ve seen no adverse reactions.

our department has fairly conservative practices though. we give only type-specific or type-compatible platelets to our patients, and if that is unavailable, we volume reduce them.

Thanks for your perspective, Danielle. This is a more conservative practice, obviously, but I’m sure that it works great!

Hi Danielle

I’m presuming the GB means you’re in the UK? Could you expand on what you mean by volume reducing platelets as I thought NHSBT and the other blood services were the only ones with an MHRA licence to “manufacture” and that hospital transfusion depts. Were limited to thawing frozen components

We keep 6 FFP thawed at all times for our “massive transfusion protocol.” 4 type A and 2 type AB plasmas. This is what we issue during a trauma situation when we don’t know the blood type, and as soon as we get a blood type result we switch to type specific. I’ve only experienced 2 occurrences when the patient was type B, and both times the trauma team had started using the AB plasma first and hadn’t started on the A plasma so it was an easy switch. If the ER orders emergency FP we just send up the two AB type we have available until we get a blood type.

From my perspective as a blood supplier, Joseph, 4 A and 2 AB is better than 6 AB’s!

My institution is in the process of implementing Group A liquid plasma for our local hospital use and had a question regarding titers. I have read the research articles that you recommended and was wondering what you have seen in regards to titer level cut offs for transfusion.

John, the only thing we can really say about titers is that no one agrees what the “appropriate” titer should be! If you go back and check the references above closely, you will see widely variable approaches, ranging from doing no titers whatsoever to feeling pretty strongly about specific titers. My personal experience as a blood center physician is that most facilities do NOT check titers on group A plasma, feeling that it is very rare for group A plasma donors to have high titer anti-B (further, many believe, based on experience with platelet donors, titers may not be predictive of hemolysis anyway). Each facility has to decide for itself how to approach this issue.

I’ve been asking for a while…..as a blood collection agency, why do we collect Type O FFP/FP24 at all? Why wouldn’t we maintain inventory of A, B, AB FP24, and have all of our Type O go to RPL…. ?

Thoughts?

Controversial topic, Jamie. Realistically, for routine transfusions, I think most would say that type-specific is best. Most people of non-O blood groups carry lots of free-floating A and/or B antigens in their plasma, and incompatibilities, while not cataclysmic, might not be the best thing, as antigen-antibody complexes are formed that may have negative effects. Again, in emergency situations, no big deal, but in routine situations, a group O person should probably get group O, in my view. We do have hospitals that have said just what you said, by the way! (sorry for the delayed response, by the way!)

Jamie,

Our suppliers often struggle to maintain adequate stocks of non group O plasma. Transfusing group O plasma to known group O patients definitely helps to alleviate the shortage.

Until last summer, our blood bank had no policy on transfusing out of type platelets. They would select just what we had that was going out of date the soonest.

This was until we had a technologist give two double-bag O platelets to a A patient. The patient had a transfusion reaction with noticeable hemolysis. Now we are more judicious with our dispensing of O platelets to non-O patients. Our policy is to give type-correct when we can. If we don’t have that option, we ask the physician and our pathologist to give the go-ahead for out of type.

Ethan, I think that if you surveyed transfusion services, they would tell you that putting in a requirement for pathologist and physician approval to go “out-of-type” for platelet transfusions is WAY beyond what most places feel is necessary (at least in the U.S.; I can’t speak for other countries)! There are options, of course, including checking titers on the group O platelets, doing things like volume reduction or washing if necessary, etc (some of which were discussed in my podcast interview with Dr. Magali Fontaine in BBGuy Essentials 004). Anyway, my personal practice is that I do not require such approval, as I think that people get out-of-group platelet transfusions safely every hour of every day across the blood banking world! That’s not a critique of your practice, just an observation. I’m all for keeping patients safe, and I think that blood bank directors can specify things about platelet ABO selection (and Rh selection, for that matter), that can accomplish just that (keeping patients safe), without requiring a formal medical approval. It is, of course, up to the individual facility to decide. Thanks for writing!

-Joe

“I think that people get out-of-group platelet transfusions safely every hour of every day across the blood banking world! That’s not a critique of your practice, just an observation.”

I disagree profoundly. There are two older randomized trials demonstrating that ABO out of group platelet transfusions lead to a 2-5 fold increase in refractoriness. Refractoriness is pretty much a death sentence in acute leukemia when it occurs due to both HLA sensitization and ABO mismatched transfusions. After adopting both leukoreduction and ABO identical (or plasma reduced) transfusions, our use of HLA matched platelets went from 500-600 per year to 20-40 per year, and we are a pretty sizable transplant and hematologic malignancy referral center.

Observational data suggest that so-called universal donor AB plasma increases the death rate in group O recipients as well as the incidence of ARDS and sepsis in trauma patients. ABO mismatched platelets may quadruple the mortality rate, and the bleeding rate by 50% in cardiac surgery patients. There is an extensive literature on the subjects reviewed in:

ABO matching of platelet transfusions – “Start Making Sense”. “As we get older, and stop making sense…” – The Talking Heads (1984).

Blumberg N, Refaai M, Heal J.

Blood Transfus. 2015 Jul;13(3):347-50. doi: 10.2450/2015.0001-15. Epub 2015 Feb 2

It’s freely accessible :).

Hi, Dr. Blumberg! I am well aware of your strong feelings on this (I read your excellent editorial referenced above a couple of years ago and have heard you speak), and am not trying to minimize the potential impact of out of group platelet or plasma transfusions. However, I also do not believe our current blood supply system is set up for provision of ABO-identical platelets or plasma for every recipient in every hospital, simply due to logistical and inventory constraints. That’s not anything but reality, in my view (and I spend my days as a blood center doc trying to make that NOT true!). Most facilities also do not have the incredible washing capabilities that you have established in your practice and described eloquently in publications. I have said many times that I believe that ABO-identical is best, but if it’s non-identical or nothing in a patient truly in need, then I know what I would choose. I would love for that to be manageable for everyone. I value and respect your opinions highly, and am honored that you took the time to comment.

-Joe

Thank you for your kind words Joe. The problem with ABO non-identical platelets is that they are given to treat or prevent bleeding, but they do exactly the opposite in many cases. Both epidemiologic clinical data and in vitro data support the hypothesis that they interfere with platelet function by direct binding to platelets (anti-A to A on platelets if the donor is O and the recipient A) and by immune complex formation. We now have data (unpublished) that these immune complexes cause endothelial damage in vitro. So giving ABO non-identical platelets is probably worse than no platelets at all in some situations.

To me the issue is simple. We can make whole blood platelets fairly cheaply (they are a “scrap product.” Overproduce them and let them outdate if need be. It would be cheaper by far than apheresis platelets, which offer essentially no clinical benefit beyond whole blood platelets. If you pathogen reduce the whole blood platelets they are probably safer than apheresis platelets because dangerous donors only contribute 50 ml to the transfusion rather than 250ml.

Alternatively, every hospital that takes care of critically ill patients who need platelets need to buy a cell washer and train their staff to wash red cells and platelets when necessary. We do lots of complex and expensive things to protect patients, and this would be one more. Another possibility is a closed system washed (such as the ACP215 from Haemonetics). Wash O platelets at the blood center and send them out in platelet additive solution with 24 or 48 hour dating to the hospital that needs them. Just some thoughts other than “we’ve always done it this way” or “it’s too hard.” It’s clearly achievable if we accept that our current practices are harming patients, and we have the will to advocate for safer, more effective transfusion practices to our administrative masters ;). We will save lives and reduce suffering by finally paying attention to ABO beyond the risks of massive hemolysis. Which are certainly there, if rare.

Dr. Blumberg, as always, you make salient and wise points. I am completely in favor of the use of whole blood derived platelets; in fact, that is why my very first podcast was a discussion with Mark Yazer on blowing away the mostly self-inflicted myths that have developed about their use. Thanks for the rest of your thoughts, as well. I completely agree that all centers and hospitals should look closely at this issue and consider options carefully.

-Joe

Thanks again for your kind comments Dr, Chaffin. I should also add that I have come around to the thinking that group A plasma makes more sense than AB, albeit for different reasons than most would think. Obviously ABO identical is safest and most effective. However, if it is impossible to get a timely sample and massive transfusion is required, A is likely safer and more effective in all likelihood. For one thing, it’s identical for 40% of patients, whereas AB is identical with 5%. And compared with O plasma, it has no anti-A, which is the most dangerous isoagglutinin in terms of hemolysis and titer. So The move to A plasma makes good theoretical and practical sense. And apparently it’s no worse than AB. AB in large volumes is probably very dangerous when given to O individuals who have high titers of anti-A to make large amounts of immune complexes. In the large Swedish database, group O patients who receive 5 or more AB plasmas have a 10% incraesed mortality rate (Shanwell, Vox Sanguinis 2009 May;96(4):316-23).

Does being a secretor sensitise other people in contact to those ABO antigens?

I want to thank you on behalf of my classmates and me. it’s bcoz of your videos, podcasts that our concepts of blood banking is clear… otherwise, we did not have any formal lectures and were struggling big time to understand the basic concepts! Thank-you once again! 🙂

I’m honored to help you and your classmates, Namita! Best of luck!

-Joe

My helicopter EMS program in Cincinnati (UC Health Air Care) has carried Type A liquid plasma for 4 years now, with no appreciable transfusion reactions despite having now given it to hundreds of patients in hemorrhagic shock. Our blood bank cautions us against giving it patients who are less than 50kg, I guess with the thought that the anti-B antibodies won’t be as diluted since the pt’s overall blood volume is less. Which sucks when you’re treating a kid who’s bleeding to death. Are you aware of any evidence for this weight-based prohibition? Thanks so much for doing what you do.

Thanks for the feedback, Bill. As far as any specific evidence for limiting use in smaller patients, well, you have to understand that the evidence for most of the process of using group A plasma in emergencies is in it’s early stages! I talked about the two most important studies with the lead authors of both (see Episode 036 of the BBGuy Essentials Podcast for more). The short version is that I understand why a blood bank would limit use of incompatible plasma in smaller patients, as the worst hemolysis we have seen in people getting incompatible out-of-group platelets has been in children (granted, with group O platelets, not group A), but there’s no evidence I am aware of that it is unsafe with group A plasma in pediatric trauma. While that may sound like I’m taking “your side” on this, I should also tell you that I’m unaware of any evidence to say it’s SAFE, either! So, this is really up to local policymakers to decide, and I would encourage you to talk with the medical leaders of your blood bank to get their perspective (and for them to hear yours!).

-Joe

Joe. Any update on the use in pediatric patients or weight-based use. I have seen cut offs of 6 years, 11 years, 15 years, and 16 years/50 kg. If there needs to be a cut off, weight-based would seem more accurate than age, but 50 kg seems very conservative. After 4 years, is there more information? Thanks, Jim

I served two tours in Afghanistan as an ER nurse and we rarely had AB plasma -all I ever gave was type A! I never saw any adverse reactions to uncrossmatched A plasma. I’m interested to see if this practice will extend further into the civilian setting. I have only given AB to traumas at my current civilian hospital.

Maura, thanks for your perspective and for your service! I believe this practice already IS extending pretty widely into the civilian sector. I see it very often in my blood center practice, especially in the larger facilities. In fact, I think group A plasma use is more widely accepted the higher the level of the trauma center (though this is anecdotal and nothing I can prove). If you haven’t already, please listen to Episode 036 of the Blood Bank Guy Essentials Podcast, where Nancy Dunbar and Tait Stevens describe their studies on this very topic.

-Joe

Such a great read!

One Day we needed plasma for a B+ patient and we had only two pints of O+ Thawed plasma and we gave it. So we started to argue about it, is it safe to continue giving the patient this plasma or giving a whole blood of the same ABO!

What do you think what will happen if we continued giving thawed plasma O type?

You’d have to make that call in your facility, but in general, the data so far shows that there is little likelihood of hemolysis with small quantities of incompatible plasma. Doesn’t mean it’s a great idea to just pour a ton of incompatible plasma in (for hemolytic and potentially other reasons), but in small quantities, the risk doesn’t seem to be massive.

-Joe

What is the potential hemolysis risk in giving a type O neg patient A pos, B pos and O pos plasma simultaneously? What is the potential mortality rate? How long should patient be monitored for potential adverse immune response and hemorrhagic risk? In other words at what point is the patient “out of the woods” from the risk? Is there a hightened risk should patient receive future transfusions of any products and if so, please explain what that would be. Thank you.

Andrea, you won’t find a lot of thoroughly studied data on the absolute risk in those situations. “Traditional” blood banking thought is this: “Protect the red cells at all costs!” Since giving group A or B plasma to a group O recipient doesn’t have a risk of immediate hemolysis (those group O RBCs don’t hemolyze from anti-A or anti-B present in those plasma products), many blood bankers wouldn’t worry about it at all, and would not limit future transfusions. However, there is data showing worse outcomes in patients who receive out of group platelet and plasma transfusions, as the great Dr. Neil Blumberg has pointed out repeatedly on this site and in his published materials. Quoting Dr. Blumberg: “In elective transfusion settings, we propose that the only truly “universal donor” and maximally effective and safe plasma is almost certainly ABO-identical plasma. The use of ABO nonidentical plasma and plasma-rich components such as platelets has been associated with adverse clinical events, including mortality.” (Transfusion 2018;58:829-831). The short answer (too late) is that while there are likely very few immediate effects of the situation you are proposing, and group A and O plasma transfusions to group O patients (and group B and AB) happens every day in trauma settings without obvious problems, we don’t truly know the longer-term effects, because they haven’t been studied in randomized trials, to my knowledge.

-Joe

Is A plasma acceptable for a pediatric (not neonatal) MTP when blood type is unknown?

To my knowledge, there is not a ton of data on that question at this point, Melissa. I believe most places that use group A plasma for emergency transfusions before the blood type is known limit the practice to “adult” patients. The two large 2017 studies that evaluated safety of group A plasma looked at transfusions to patients age 15 and older in one study (Stevens et al, J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2017;83(1):25-29), and as far as I can tell, included patients down to age 11 in the other (Dunbar et al, Transfusion 2017;57;1879–1884). By the way, I discussed these studies with the authors in Episode 036 of the Blood Bank Guy Essentials Podcast in 2017. Neither study focused on the pediatric population, of course. I’m not saying giving group A as a starting point in emergency pediatric massive transfusion is a bad thing to do, just that I don’t know that we have data to support or discourage it at this point.

-Joe

Melissa – what did you wind up doing? Did you give A plasma to pediatrics MTP cases?

Joe, any new data since your response to Melissa almost two years back on this? There have been a few recent publications on pediatric MTP but not on giving A plasma in such scenarios. We are struggling with this on our service and are considering providing A plasma to peds MTP (similar to adult) in light of AB inventory fluctuations and frozen vs thawed inventory considerations. Any thoughts are welcome.

Glad I came across this – it satisfied my curiosity! I gave platelets for the first time yesterday and am A negative. They asked if I could also give plasma. I said sure, but thought it was odd with my blood type and now I understand more about why!

Thanks!

I wonder how you feel plasma exchange should be handled when AB plasma supplies are limited and your patient is group O or B? I have seen one paper suggesting approximately 46% of the plasma can be non-AB low titer group A

As always, Thank you for a wonderful resource.

Hey Kip. Great to hear from you, as always. I’ve certainly seen group A used in that setting, tilted more toward the beginning of the exchange and saving the AB for more toward the end (logical, right?). I’m not sure that I really believe there is an exact number or percentage that is “safe” vs. “unsafe,” though. Like many things in our field, this is one that I think has practice variations. I’d welcome any further comments from others practicing therapeutic apheresis on a more regular level than me (it’s been a little bit since it was day-to-day for me).

-Joe