This episode comes in two parts, recorded a couple of months apart to reflect what was happening in 2016 with testing for Zika virus.

Dr. Joe Chaffin

IMPORTANT NOTE: Things have changed pretty dramatically since I recorded the first Zika podcast in July 2016! In August 2016, FDA released a guidance that “recommends” that ALL U.S. blood donors are tested for Zika, using the investigational nucleic acid test mentioned in the podcast. This will change how blood centers approach the issue substantially. The update above briefly discusses what has changed.

FINAL UPDATE: In May 2021, the FDA pretty much made this entire discussion moot by declaring in a Guidance that Zika is no longer a “relevant transfusion-transmitted infection.” Since no US blood donor had tested positive for ZIKV since 2018, the FDA allowed US blood centers to stop testing for the virus, and most did so in mid-2021. The discussion in this episode is still relevant, however, as the “why” behind what the FDA did is important. Please be aware of the above, however, and understand that when you read these words and hear this episode, the ZIKV facts have changed.

Original Introduction: Talk of Zika has been pretty much everywhere for most of 2016, with athletes declining to participate in the Olympic Games, and pregnant ladies concerned about their unborn children. The blood industry has taken steps to reduce for the possibility of transmission through transfusion, as well. Until now, however, Zika in the U.S. was primarily acquired by travelers to countries where the Aedes aegypti mosquito is transmitting the virus from one person to another (i.e., “local transmission”). On July 29, 2016, the Florida Department of Health and the Centers for Disease Control essentially confirmed local transmission in a very small area in South Florida. This changes the game for blood collectors, and this podcast is recorded in response to numerous questions. We discuss the virus in general, the clinical issues associated with it, and the blood industry’s response moving forward. This episode is NOT an official position statement, just an educational summary for interested listeners.

Dr. Joe Chaffin

FINAL UPDATE: In May 2021, the FDA pretty much made this entire discussion moot by declaring in a Guidance that Zika is no longer a “relevant transfusion-transmitted infection.” Since no US blood donor had tested positive for ZIKV since 2018, the FDA allowed US blood centers to stop testing for the virus, and most did so in mid-2021. The discussion in this episode is still relevant, however, as the “why” behind what the FDA did is important. Please be aware of the above, however, and understand that when you read these words and hear this episode, the ZIKV facts have changed.

Original Introduction: Talk of Zika has been pretty much everywhere for most of 2016, with athletes declining to participate in the Olympic Games, and pregnant ladies concerned about their unborn children. The blood industry has taken steps to reduce for the possibility of transmission through transfusion, as well. Until now, however, Zika in the U.S. was primarily acquired by travelers to countries where the Aedes aegypti mosquito is transmitting the virus from one person to another (i.e., “local transmission”). On July 29, 2016, the Florida Department of Health and the Centers for Disease Control essentially confirmed local transmission in a very small area in South Florida. This changes the game for blood collectors, and this podcast is recorded in response to numerous questions. We discuss the virus in general, the clinical issues associated with it, and the blood industry’s response moving forward. This episode is NOT an official position statement, just an educational summary for interested listeners.

More a question than a comment:

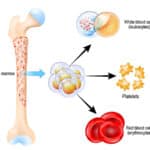

I am a bench tech in our local hospital’s transfusion servicein upstate New York. We had a visit yesterday from a representative of our blood products supplier, when he announced that our pooled platelets (and soon our frozen plasma) will now be supplied to us as being pathogen-reduced by a process that will destroy the Zika virus DNA. (He was throwing terms like chemo/bioluminescent technologies that neither I nor he really understood.)

Now for the questions:

If we are able to destroy or incapacitate the viral DNA from Zika, why can’t it be done for other viruses, for example hepatitis or HIV? And if the methodologies used to destroy the virus are specific to that virus, arent we worried about mutations occuring in the viral DNA/RNA that would make those proteins unrecognized by our current methods?

Lynn, the technology that you mentioned, pathogen reduction, is not specific for Zika. It deactivates the nucleic acids of nearly all organisms that we know of, including hepatitis viruses and HIV, as you mentioned. Not only that, it deactivates the DNA in donor white blood cells in the unit, so it eliminates the need to irradiate pathogen-reduced blood products. The technology, in other words, is nonspecific, so there really are no concerns about mutations making the technology obsolete. The currently approved technology in the U.S. uses a substance that binds to any nucleic acid followed by irradiation with ultraviolet light that permanently damages the DNA/RNA (again, nonspecifically; not just Zika but any DNA/RNA present).